By Melody Crowder-Meyer, Shana Kushner Gadarian, and Jessica Trounstine

When Los Angeles County voters entered their polling booths in November 2016, they were faced with a multitude of decisions. The choice of which presidential candidate to support was likely fairly straightforward. But how about voters’ choice for the U.S. Senate? Both candidates available were Democrats – how did voters determine which candidate would better represent their preferences? Further down the ballot, voters were then presented with local races. The candidates running for Board of Supervisors, Judge of the Superior Court, City Council, and Rent Control Board were all listed as nonpartisan. Making all these decisions – filling out this ballot – asked a lot of citizens. So, how do citizens generally make decisions about casting their votes when they have little information to use?

In this paper, we examine how voters make decisions under varying levels of information. Existing research clearly demonstrates that voters draw on shortcuts – heuristics such as ideology and partisanship – to substitute for full information when making voting decisions. But in non-partisan elections or in elections (like party primaries) in which both candidates share the same party identification, these heuristics can’t help. What then do voters do? We investigate the extent to which voters use candidates’ race, ethnicity, and gender – characteristics that can often be identified even in the lowest information elections – as shortcuts to help them make decisions. Importantly, our exploration is conducted in settings where partisan cues are absent, which is the case in the vast majority of local elections in the United States.

We use 3 experiments to test the way that varying the amount of candidate information affects how voters choose candidates. In particular, we are interested in whether information helps or hurts the chance that candidates of color and female candidates win. In the experiments, we asked subjects to act like voters and choose candidates in 3 elections: city council, county board of supervisors, and a parks and recreation board. We randomly assigned candidates of varying races and gender, and randomly assigned levels of information available to voters.

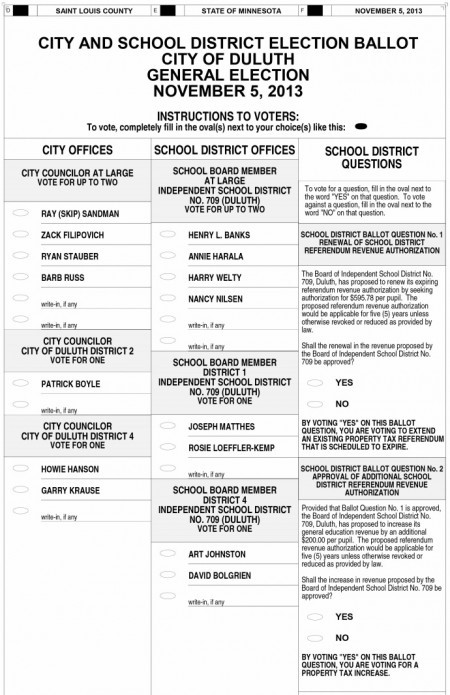

Our lowest information setting included only candidate’s names –like this ballot from Duluth, Minnesota.

Our medium level of information setting provided candidates’ occupations as well – just like this ballot from Alameda, California.

In our highest information setting, we told voters candidates’ name, occupation, age, educational background, and incumbency status.

We find that voters do indeed rely on candidate characteristics when casting their ballots. While racial and ethnic minorities lose in low information settings, women win. However, as shown in the figure below, increasing the amount of information available to voters moderates both of these effects.

More information reduces the effect of candidate race and gender on vote choice

The figure shows the difference in the probability of voting for candidates with specific racial and gender characteristics – compared to white candidates and male candidates – under conditions of low, moderate, and high information. African-Americans suffer the greatest penalty in our low information experiments, followed by Asians and Latinos. Women are given a slight benefit when voters have the least information. Adding information about the candidates reduces these penalties and benefits.

But who is most likely to rely on candidate race and gender as cues….and why? In a separate experiment, we found that voters assume that black and Latino candidates are more liberal than white candidates, and that female candidates are viewed as more liberal than male candidates. How did this affect vote choice? We find that liberals and Democrats are substantially more likely than conservatives and Republicans to support female candidates and candidates of color in our lowest information settings. In fact, the preference for women in the lowest information setting is wholly driven by liberal and Democratic respondents. Voters seem to be drawing on racial and gender stereotypes to cast their ballots in our experimental elections.

But, does any of this hold outside of the lab? To determine the extent to which our findings apply outside the experimental context, we also evaluated a set of voting choices in a real, but very low information, election – the election for presidential convention delegates. In New York State, voters in the 2016 Democratic presidential primary voted in their Congressional Districts both for the presidential candidate that they preferred, and also directly for the delegates who would support those candidates at the Democratic National Convention. Democratic party rules dictate that half of all delegates to the convention be male and half female, so delegate candidates were equally divided by gender, mimicking our experimental design. In addition, voters had very little information about these delegates except for their names and their gender.

Each delegate on the ballot was pledged to one of the presidential candidates, but some of the ballot designs made that easier to understand than other ballots. We take advantage of this difference in ballots across counties to predict that any advantage given to female delegates should disappear when delegates are clearly linked to candidates (essentially, when we move from a very low information condition to a more moderate information condition). This is exactly what we find. As the figure below highlights, even in real world elections, more information decreases gender of candidate effects on vote choice.

Ballot clarity helps male delegates in NY State presidential primary

In sum, using three experiments and one real-world election, we show that when voters are forced to make decisions without any information about the candidates other than their names, they use the names to figure out who to pick. Adding information to voters’ ballots largely eliminates these penalties. Small amounts of virtually costless information decrease voters’ use of demographic traits to make decisions. In our real-world example simply clarifying the delegate’s pledged candidate largely eliminates the effect of gender and adding occupation to our experimental ballots significantly reduces the effects of race. Should a broader set of states adopt ballots with additional contextual information about candidates (as shown in the Alameda, California ballot above), or if media trends changed such that (especially local) political information was more widely accessible and consumed by voters, this could substantially affect the ways that voters make decisions about who governs them – at the local level and beyond.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MBjGMmoqywM?rel=0&controls=0]

About the Authors: Melody Crowder-Meyer is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Davidson College, Shana Kushner Gadarian is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University, and Jessica Trounstine is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Merced. Their research “Voting Can Be Hard, Information Helps” presented at the 2017 MPSA conference, received the association’s inaugural Best Paper in American Politics.